Reclaiming Wild Rice: Helping Indigenous Communities Develop More Secure Food Sources

"Wild rice is culturally, nutritionally, and economically significant to the Anishinaabe people of the Great Lakes area," says Lakehead Adjunct Biology Professor Dr. Vincent Palace.

According to their creation story, the Anishinaabe migrated inland from the eastern seaboard to the place where food grows on the water—that food was wild rice, or "manoomin" in the Ojibwe language.

Dr. Palace—who is also the head research scientist at the International Institute for Sustainable Development-Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) research station about 60 km north of Kenora, Ontario—is part of an exciting research initiative focused on wild rice.

The MANOOMIN project, which stands for Multi-culture Agribusiness for Northern Ontario Managed by Indigenous Nations, is a collaboration between the Myera Group (an Indigenous-led biotechnology company committed to fostering Indigenous food sovereignty), IISD-ELA researchers, Lakehead University, and several Treaty #3 Indigenous communities in northwestern Ontario.

"The Kenora Chiefs' Advisory, a cooperative of eight communities from the Treaty #3 area, are part of this project, and they've been amazing to work with!" Dr. Palace says.

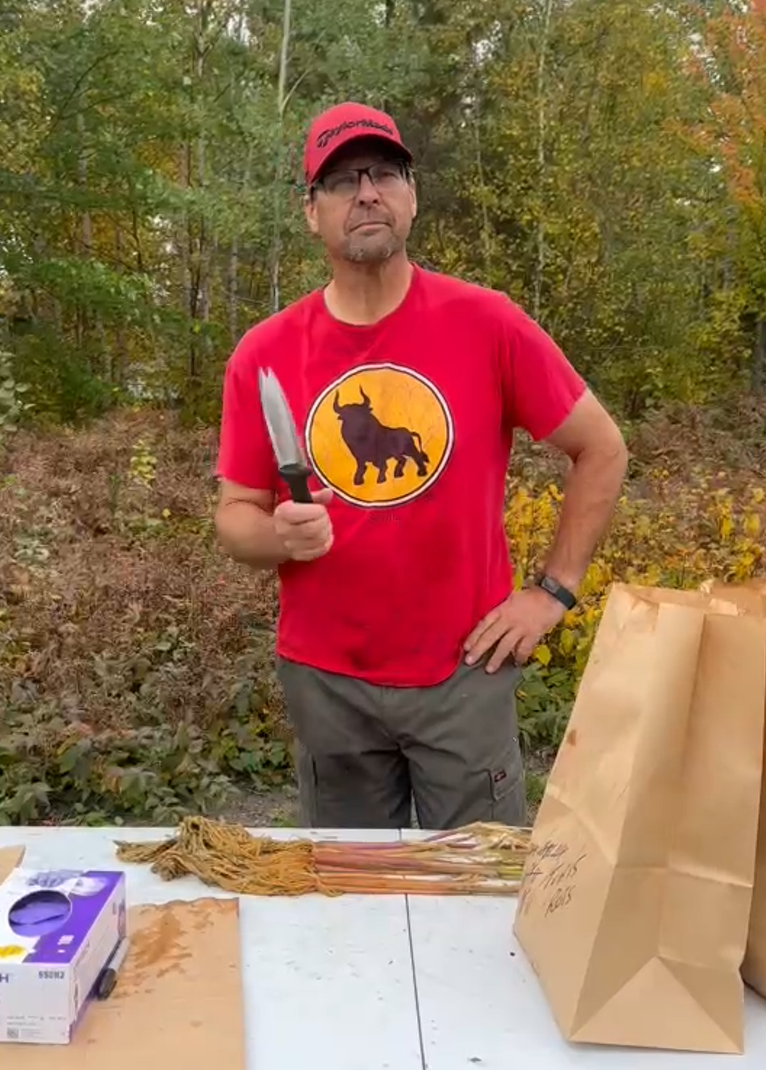

Dr. Vincent Palace (left) processing wild rice. Dr. Palace’s research group is currently examining the effects of competition from cattails on wild rice. They’ve also studied how water levels affect the productivity of wild rice.

"Traditionally, most communities harvest this sacred food by canoeing among stands of wild rice growing in lakes, pulling wild rice plants over their canoes, and rapping them with a stick to knock the rice into their boats. This harvesting method means that some of the rice grains fall into the water, allowing the plants to reseed themselves every year."

Despite the importance of wild rice to Indigenous people, accessing and harvesting it has become more difficult. Hydroelectric production in northwestern Ontario's Rainy River system, for instance, has destroyed habitats where wild rice was typically harvested, and this destruction has been compounded by the spread of an invasive species of cattails that is choking out wild rice. An additional pressure comes from the increasing age of wild-rice harvesters and the growing danger that their knowledge will be lost. "The time to train younger generations to harvest rice and to remove the cattails is limited," Dr. Palace explains.

Wild rice is a nutritionally dense food that’s low in fat and high in fatty acids and fibre. Moreover, wild rice stands create higher-quality habitats for fish, birds, and other animals compared to habitats dominated by cattails.

The research team plans to strengthen these communities' food sovereignty by establishing fish farms in their territories that will be owned and operated by community members. The fish farms will have a dual purpose: the fish will provide an important food source and the solid and liquid waste they excrete will be used as a fertilizer to grow wild rice and traditional medicine plants. Fish waste contains ammonia and phosphorus—nutrients that wild rice plants need to grow. Myera will contribute its business expertise by helping the communities produce wild rice flour, rice cakes, protein shakes, bannock, and other foods for their own consumption, as well as for distribution and sale outside these communities.

Around 50 per cent of the wild rice consumed in Canada is, in fact, commercially cultivated wild rice imported from the United States. The flooded paddies this rice is grown in generates large amounts of methane gas. That's why MANOOMIN researchers are experimenting with growing rice in shallower water to reduce methane production. According to the IISD-ELA, a 10 per cent reduction in emissions would be equivalent to removing 10 million vehicles from the road.

"The overarching idea of marrying fish aquaculture and waste with wild rice production originated with Myera," Dr. Palace says, "although a lot of the work we're doing is based on the research of retired Lakehead biology professor Peter Lee."

MANOOMIN has just completed its third year and is now investigating how different wild rice varieties compete with cattails for nutrients. Next, they'll remove cattails and replace them with wild rice.

"As a scientist, doing research that will be useful to communities is very gratifying," Dr. Palace says.

The MANOOMIN project is possible because of the support of the Myera Group, Northern Ontario Heritage Fund, Protein Innovation Supercluster, and Lakehead University.