Alum Dr. Amy Junnila Fights the Insect that Brings Pestilence and Death

Solving the mysteries of the fabled Titanic shipwreck is something most people can only dream of, but that's exactly how Dr. Amy Junnila began her research career in the late 1990s.

As an undergraduate anthropology student, Dr. Junnila was part of a team at Lakehead's world-renowned Paleo-DNA Lab that helped identify victims of the maritime disaster who'd lain buried and unknown in a Halifax, Nova Scotia, cemetery.

Lakehead's Paleo-DNA Lab offers outstanding modern DNA services as well as degraded and ancient DNA analyses. Adjunct Professor Dr. Junnila (HBSc'00/MSc'02) will continue some of her work in DNA analysis at the laboratory.

"I'm thoroughly grateful to Lakehead for teaching me everything I know about DNA," says Dr. Junnila, who also earned a Master of Science in Biology specializing in wildlife parasite DNA at Lakehead. "The Paleo-DNA Lab is an international leader in the analysis of degraded and ancient DNA."

Born and raised in Thunder Bay, Dr. Junnila completed a PhD at McGill University and a post-doc at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem before moving to Africa to continue her work with an international research team she joined in 2006 while in Israel. "The team—which has members in Mali, Greece, Russia, Israel, and Florida—is dedicated to dramatically reducing mosquito populations in Mali, West Africa, where mosquitoes carrying malaria are a huge health risk," Dr. Junnila explains.

"We collect flowers that mosquitoes feed on and give them to researchers in another lab to make the scent extracts we use in our mosquito-control system," Dr. Junnila says.

She has recently returned to Lakehead as an adjunct professor in the Department of Anthropology and reconnected with the Paleo-DNA Lab, where her work is enhancing Lakehead's already strong commitment to meeting the United Nations' 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These goals are a universal call to action to build a better future for everyone, and Dr. Junnila's research is advancing SDG 3, aimed at ensuring good health and well-being around the globe.

Her research team is supported by the Innovative Vector Control Consortium subgroup of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. "Their funding gives us the resources for all of the complex moving parts," Dr. Junnila says.

The Scourge of Malaria

Malaria is an ancient disease transmitted to humans after they've been bitten by female Anopheles mosquitoes whose guts are the home of a single-celled parasite in the Plasmodium family. Every year, malaria kills approximately 600,000 people, with Africa suffering the highest death rates. Tragically, most of the casualties are children under five years old.

Symptoms of malaria include fever, vomiting, seizures, and diarrhea. It also damages blood cells, which can cause organ failure, brain swelling, and death. Since the parasite constantly mutates, it's able to hide from the human immune system, making it extremely hard to formulate an effective vaccine.

Dr. Junnila trapped these mosquitoes during her fieldwork in Mali. Before capturing them, she sprayed flowers in the area with different colours so that she could determine which plants the mosquitoes were feeding on.

"Malaria was widespread in the United States until the early 1900s when they began draining wetlands and standing water where mosquitoes lay their eggs and developed antimalarial medications," Dr. Junnila explains. It's not only swampy places where malaria flourishes. Arid farming regions in Mali, where rice crops are irrigated, for example, attract mosquitoes.

"Mosquitoes are the apex predators of humans," Dr. Junnila says. "In addition to spreading malaria, they carry yellow fever, dengue fever, Zika virus, and West Nile virus. Mosquitoes are equally dangerous to dogs because they carry the parasite that gives them heartworm."

To overcome this threat, Dr. Junnila is studying the plant-feeding behavior of the Anopheles mosquito and then using this information against them. "Mosquitoes, like hummingbirds, beat their wings very quickly and fly around a lot," Dr. Junnila says, "this makes them dependent upon sugar to survive. Flowers are their number-one food source—it's like giving them a Snickers bar."

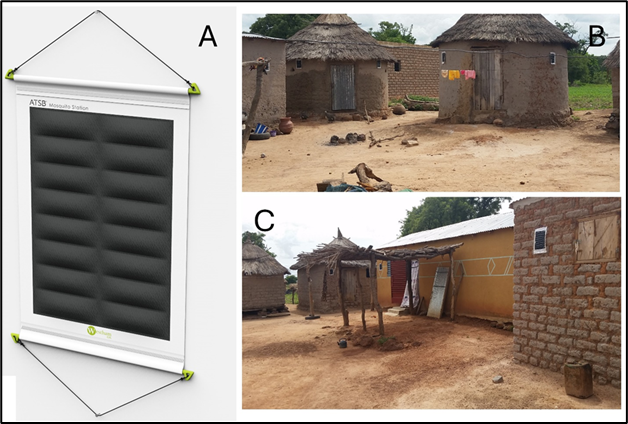

Her research team has devised the Attractive Toxic Sugar Baits (ATSB) mosquito-control system—consisting of feeding stations containing a paste made of sugar water, an insect-specific poison, and a floral scent that appeals to mosquitoes—as a way to reduce mosquito populations.

Left is a prototype of the Attractive Toxic Sugar Baits (ATSB) mosquito-control system and images of a village in Mali where it was tested.

The initial results are impressive. "We had an industry partner that helped us create feeding stations we hung on every home in selected villages in Mali—the stations were able to eliminate more than 80 per cent of mosquitoes in the area."

Dr. Junnila cautions, however, against getting rid of all mosquitoes.

"Since mosquitoes land on flowers, they're probably acting as pollinators. That's why it makes me nervous when people talk about eradicating them entirely; doing so would be ecologically devastating and could destroy crops people depend upon."

One of the ingenious aspects of the ATSB system is that the toxic paste is covered with a plastic-like membrane that mosquitoes can pierce with their mouth parts, which, conversely, is too thick for other pollinators like bees and butterflies to penetrate, keeping them safe.

The researchers are currently in the process of using DNA fingerprinting to pinpoint the flowering plants that mosquitoes prefer to recreate these scents in the lab. Their ultimate goal is to export this technology to any part of the world dogged by malaria—including Asia, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and the southern United States—and end the high toll that mosquitoes take on human lives.

Although the Culex mosquito found in Canada doesn't carry malaria and the average Canadian probably doesn't spend much time thinking about this disease, with our warming climate, the Culex mosquito carrying West Nile virus could well make its way east and north to Ontario. "That's why one of my aspirations is to have Lakehead join the fight against mosquitoes," Dr. Junnila says.

Lakehead University is ranked in the top 10 per cent globally for universities making an impact through a commitment to sustainability and positive societal change, and was named the top-ranked university with under 10,000 students in Canada and North America in the Times Higher Education Impact Rankings. These prestigious rankings assess universities' success in delivering on the United Nations 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to solve our planet's most pressing social, economic, and environmental challenges.