Research in Action: Unlocking new sources of energy to keep the grid humming

Published in The Chronicle Journal Thursday, December 15, 2022

BY JULIO HELENO GOMES

Pursuing an education in machine learning and big data analysis, coupled with a blossoming interest in smart grids, has led a Lakehead University student to develop software that is now being used by the region’s largest electricity provider to meet high-energy demands and possibly pave the way to a greener future.

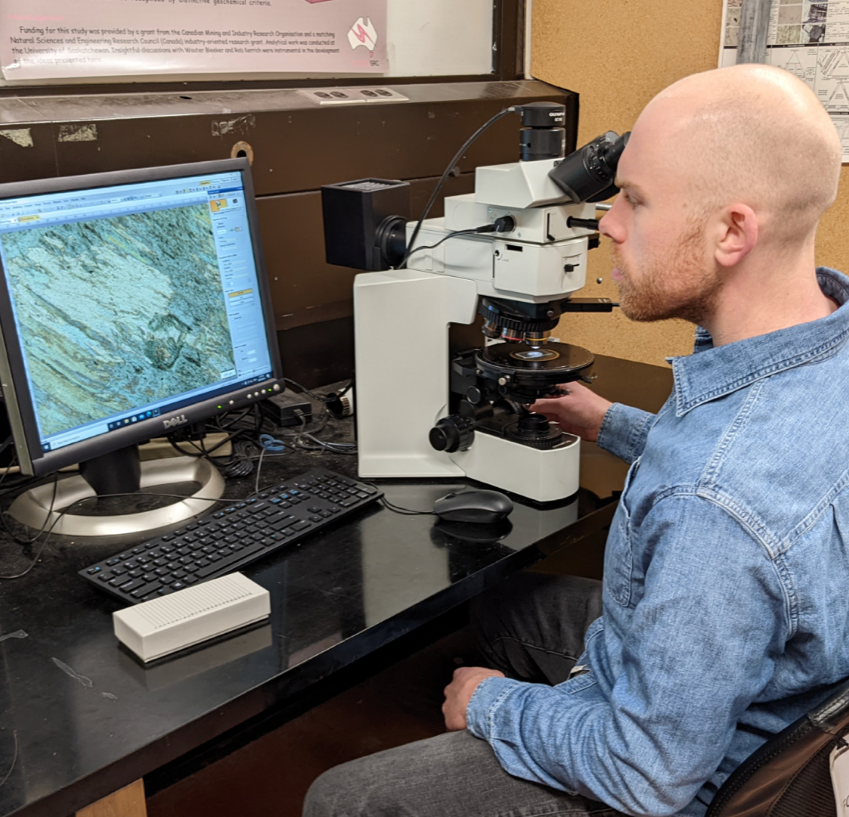

The project to help predict peak load consumption, especially on season-changing days, was the focus of a master’s thesis by international student Jiawei Dong. Over the course of this work, he analyzed reams of data, wrote mathematical models in code, tested it, and developed algorithms for the software that has just recently been installed by Synergy North.

“From end to end, he’s the one who’s done everything,” states Dr. Abdulsalam Yassine, chair of Lakehead’s department of software engineering.

Yassine supervised the project to develop data analytics for adaptive demand response in smart grids. The work was funded by a $60,000 grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Alliance Program. Synergy North contributed a further $30,000.

“Synergy North was looking to investigate distributed energy resources and how they can be integrated with the distribution grid,” explains Andy Armitage, Synergy North vice president of customer and information services. “The experience proved invaluable as we are now expecting the proliferation of these resources in the near future.”

Armed with 10 years of data on energy consumption from among Synergy North’s 50,000 residential and 6,000 commercial customers in Thunder Bay and Kenora, Yassine and Dong used artificial intelligence to predict when demand would be highest so they could schedule the discharge of batteries into the system at optimal times. These batteries, the size of large bookcases and weighing close to 500 lbs., are in three prototype houses that use solar panels to generate up to 11 kilowatt-hours of energy, enough to run a sump pump or fridge.

“In order to avoid the costs of buying energy at the peak time they would schedule batteries inside these homes to compensate for some of the energy in the grid,” Yassine says. “But they need to know exactly when to use them.”

Energy consumption fluctuates throughout the day and varies from the weekday to the weekend and on statutory holidays. As well, there is the “shoulder season,” the transition during spring and fall when temperatures can swing from a daytime high of 20-degrees Celsius to -20 C overnight.

“It makes the prediction of the peaks very difficult,” says Armitage, “because a lot of it is based on the weather.”

Over the course of two years, Yassine and Dong collected the data, developed the algorithms, tested and then deployed them at the three prototype houses.

Dong, who has had a long-time interest in AI and machine learning, also read technical papers on smart grids to try different ways to improve performance.

“We proposed a day-ahead energy forecasting system and a distributed energy resources discharging scheduling system. We also proposed some novel ideas to improve forecasting accuracy during the ‘shoulder’ season,” says Dong, who graduated with a master’s degree in electrical and computer engineering.

“I think saving resources is very valuable to the community.”

For Synergy North, Yassine and Dong’s findings help them learn more about how these different resources can be used in the electricity system. The concept of “distributed energy resources” is that energy is provided by different sources and doesn’t come from one central place, for example, a hydro-electric power station.

“So you don’t have to rely on the one point of generation,” states Armitage. “If we have several distributed energy resources on the grid they can all kind of work together to make it a little more resilient and robust.”

The benefit to Synergy North is not just to reduce the cost of buying energy to meet surges in demand. By having more sources available to feed the grid, it can also defer maintenance and upgrade costs.

While the savings are not insignificant, there is another benefit.

“The potential is in scaling,” says Yassine. “That could include electric vehicles, electric buses, commercial customers, more residential customers with solar panels and batteries. That’s the potential. The solution stays the same. Now it’s for Synergy North to find more participants in this project. Instead of having three batteries, they could have, for example, 50 batteries from different houses.”

This project is at an end and funding has been confirmed for a new study that will examine the electrification of public transit. That project, which involves Synergy North, the city of Thunder Bay and Blu Wave-ai, will look at the impact of energy consumption if diesel buses are replaced with electric buses. What is the impact on the grid? Can you discharge batteries to the grid using the same system?

For Synergy North, these collaborations with Lakehead University can help unlock new ways to keep the electricity grid humming.

“We believe in the not-too-distant future these distributed energy resources will become more readily available,” Armitage says. “If we’re not part of the process of having these on the grid and using them, the full value of it doesn’t get used.”

This project is also an example of how universities and their partners are contributing to the achievement of the following UN Sustainable Development Goals: Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy, Goal 9: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, Goal 13: Climate Action and Goal 17: Partnerships for the Goals.

Research in Action highlights the work of Lakehead University in various fields of research.

Elise Agnor, a research assistant with Gokani, completed the shelter surveys. She spoke to more than 100 people who were staying at either Shelter House or Salvation Army. That was followed by one-on-one interviews with 18 individuals to ask more detailed questions about why they came to Thunder Bay, whether they planned on staying, and the barriers to returning to their home community.

Elise Agnor, a research assistant with Gokani, completed the shelter surveys. She spoke to more than 100 people who were staying at either Shelter House or Salvation Army. That was followed by one-on-one interviews with 18 individuals to ask more detailed questions about why they came to Thunder Bay, whether they planned on staying, and the barriers to returning to their home community.

“This is an intercultural education project across several continents,” Pluim said.” Basically, we plan to investigate the implications of educational curriculum being shared between Commonwealth countries.”

“This is an intercultural education project across several continents,” Pluim said.” Basically, we plan to investigate the implications of educational curriculum being shared between Commonwealth countries.”