Research in Action: Lakehead professor's new book describes what art can teach you about money

Submitted by Lakehead University

Published in The Chronicle Journal on Wednesday, October 17, 2018

Dr. Max Haiven is interested in the power of the imagination. Now a Canada Research Chair in Culture, Media and Social Justice at Lakehead University, Dr. Haiven’s work considers the imagination in a collective sense, asking how we think about imagination and its potential for changing society. Dr. Haiven calls this the radical imagination; here, the term radical is used in its original meaning, “from the roots.”

One area where Dr. Haiven has focused his work on the radical imagination is in considering how we think about money. “Money is an abstract concept that exists only as part of a society’s collective imagination,” Haiven said. “My work asks: what metaphors do we use to make financial ideas concrete? How do these metaphors become part of our everyday lives?”

During his previous appointment as a professor at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Dr. Haiven worked with a group of students to build a database of artworks that used financial concepts in some way.

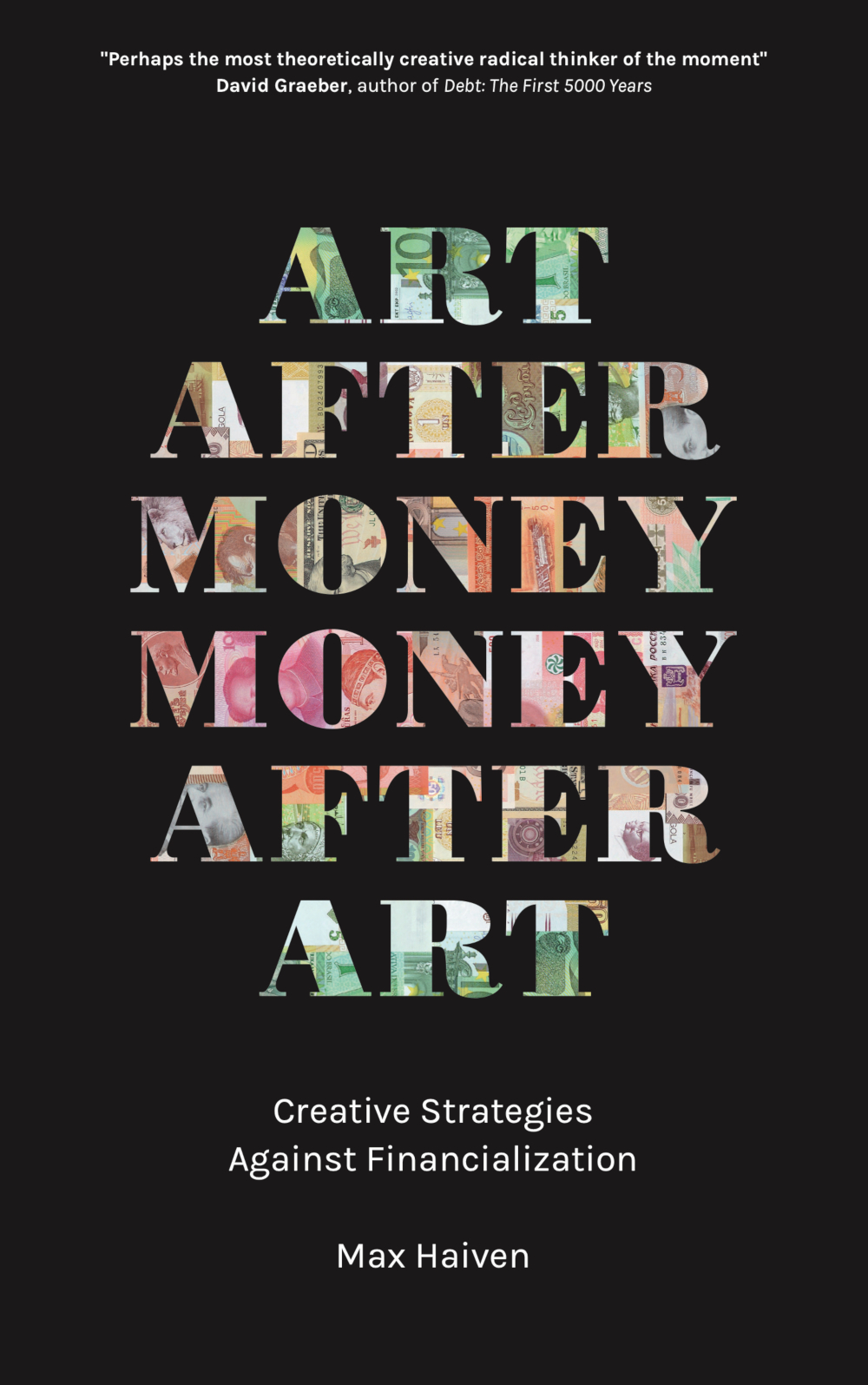

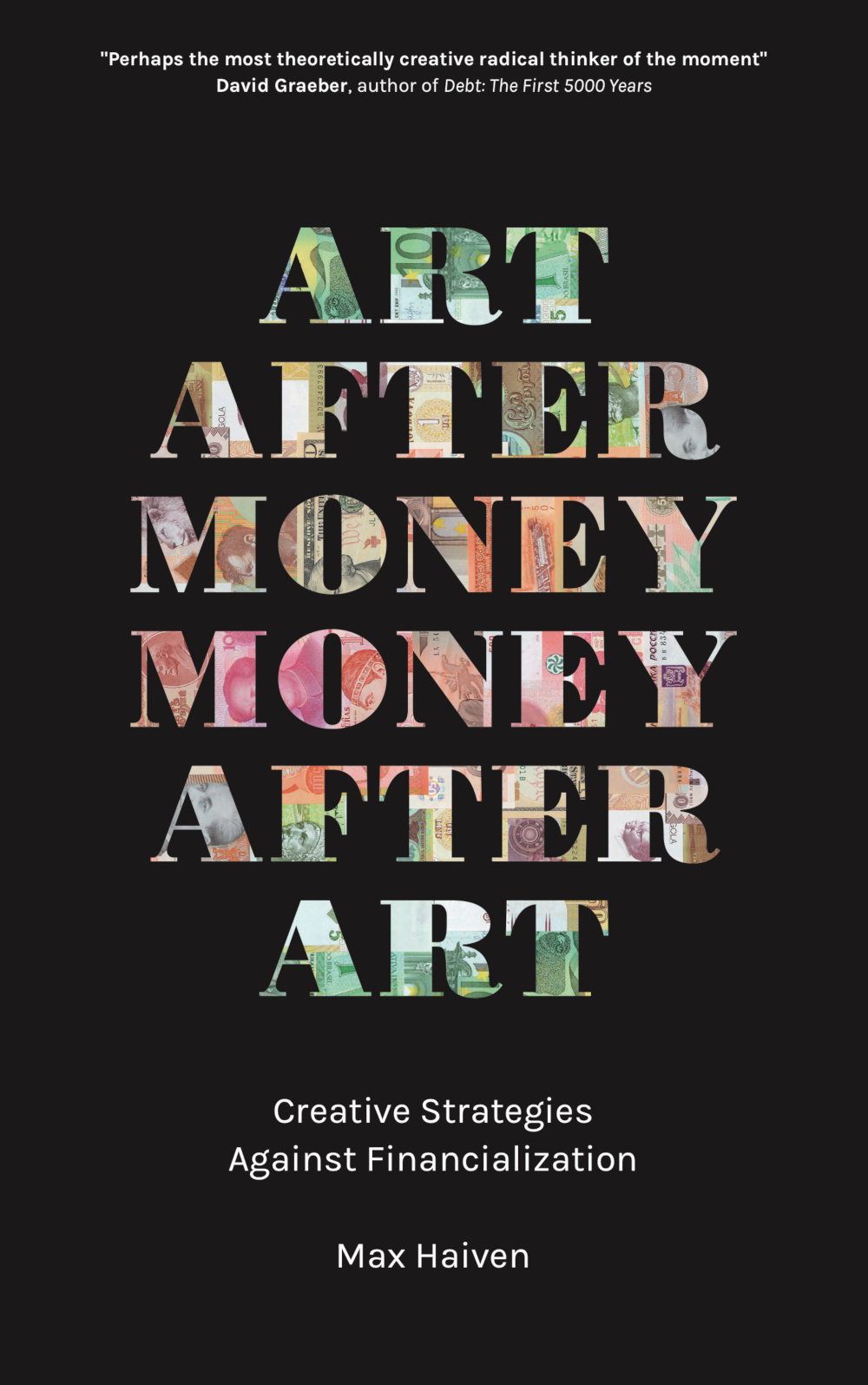

This database formed the basis for Dr. Haiven’s new book, Art After Money, Money After Art: Creative Strategies Against Financialization, which has just been released by Pluto Press and Between the Lines Books in Canada. The book examines strategies that artists use to respond to financial systems, and considers what art has to teach us about how we collectively imagine money.

While working in Halifax, Dr. Haiven co-directed the Radical Imagination Project from 2010-2016, which hosted roundtables and workshops by and for scholars, students, activists, artists and community members.

He brought this collaborative methodology to Lakehead University in 2017, where he now co-directs, with artist Cassie Thornton, the ReImagining Value Action Lab (RiVAL). Started with funds from the Canada Foundation for Innovation, RiVAL is located in Lakehead’s PACI building.

Recently, RiVAL hosted a series of workshops on radical financial literacy, which used film, games, and role-playing to re-think financial issues as structural rather than personal, and to consider how individuals might support one another through financial crisis.

In the sessions, attendees also considered models that respond or provide alternatives to current financial systems. In hosting these and other workshops, RiVAL has partnered with a number of social and arts organizations in Thunder Bay and the region, such as Thunder Bay Bear Clan Patrol, the Thunder Bay Art Gallery, and the Minneapolis Public Library.

Dr. Richard Togman is a course facilitator with Thunder Bay’s New Directions Speaker’s School, which helps people develop public speaking and leadership skills, who partnered with RiVAL to deliver a Radical Financial Literacy workshop to Speaker’s School participants.

“We previously had an accountant come in and talk about financial literacy, but it was interesting to have both this approach and a different perspective from RiVAL – to talk about debt, and how the financial system works,” Togman said.

“This was applicable to the participants in speaker school who tend to be low income and more at risk of predatory financial practices such as payday loans,” he said.

Its co-directors consider RiVAL both a research space and a community space, and are open to new ideas for co-hosting events that would fit with the ideas of the radical imagination and/or social justice.

The Thunder Bay launch for Art After Money, Money After Art will be on Friday, Oct. 19 at 2:30 pm in Lakehead University’s ATAC building, room 5036.

For a list of RiVAL’s upcoming workshops, talks and other events or to contact RiVAL, visit rival.lakeheadu.ca.

Research In Action highlights the work of Lakehead University in various fields of research.

Math is not a four-letter word. But to those with rampant math phobia, it certainly feels like it. Dr. Ruth Beatty, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at Lakehead University’s Orillia campus often sees students who actively dislike or even fear math. To her the problem isn’t with math itself, it’s with how the subject traditionally has been taught.

Math is not a four-letter word. But to those with rampant math phobia, it certainly feels like it. Dr. Ruth Beatty, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at Lakehead University’s Orillia campus often sees students who actively dislike or even fear math. To her the problem isn’t with math itself, it’s with how the subject traditionally has been taught.