Lakehead and Waterloo researchers match living descendant's DNA to remains from ill-fated 1845 Franklin expedition

The skeletal remains of a senior officer of Sir John Franklin's 1845 Northwest Passage expedition have been identified by researchers from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University using DNA and genealogical analyses.

The skeletal remains of a senior officer of Sir John Franklin's 1845 Northwest Passage expedition have been identified by researchers from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University using DNA and genealogical analyses.

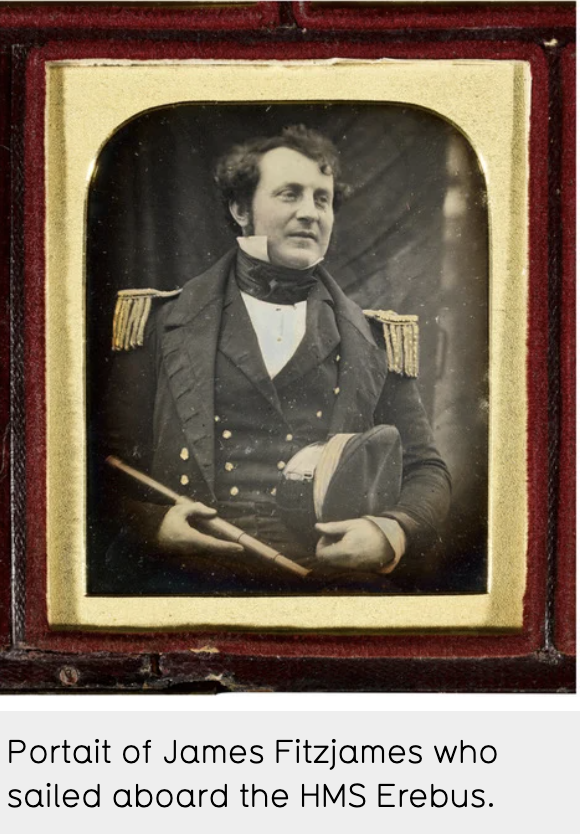

In April of 1848 James Fitzjames of HMS Erebus helped lead 105 survivors from their ice-trapped ships in an attempt to escape the Arctic. None would survive. Since the mid-19th century, remains of dozens of them have been found around King William Island, Nunavut.

The identification was made possible by a DNA sample from a living descendant, which matched the DNA that was discovered at the archaeological site on King William Island where 451 bones from at least 13 Franklin sailors were found.

“We worked with a good quality sample that allowed us to generate a Y-chromosome profile, and we were lucky enough to obtain a match,” said Stephen Fratpietro of Lakehead’s Paleo-DNA lab.

Fitzjames is just the second of those 105 to be positively identified, joining John Gregory, engineer aboard HMS Erebus, whom the team identified in 2021.

“The identification of Fitzjames’ remains provides new insights about the expedition's sad ending,” said Dr. Douglas Stenton, adjunct professor of anthropology at Waterloo.

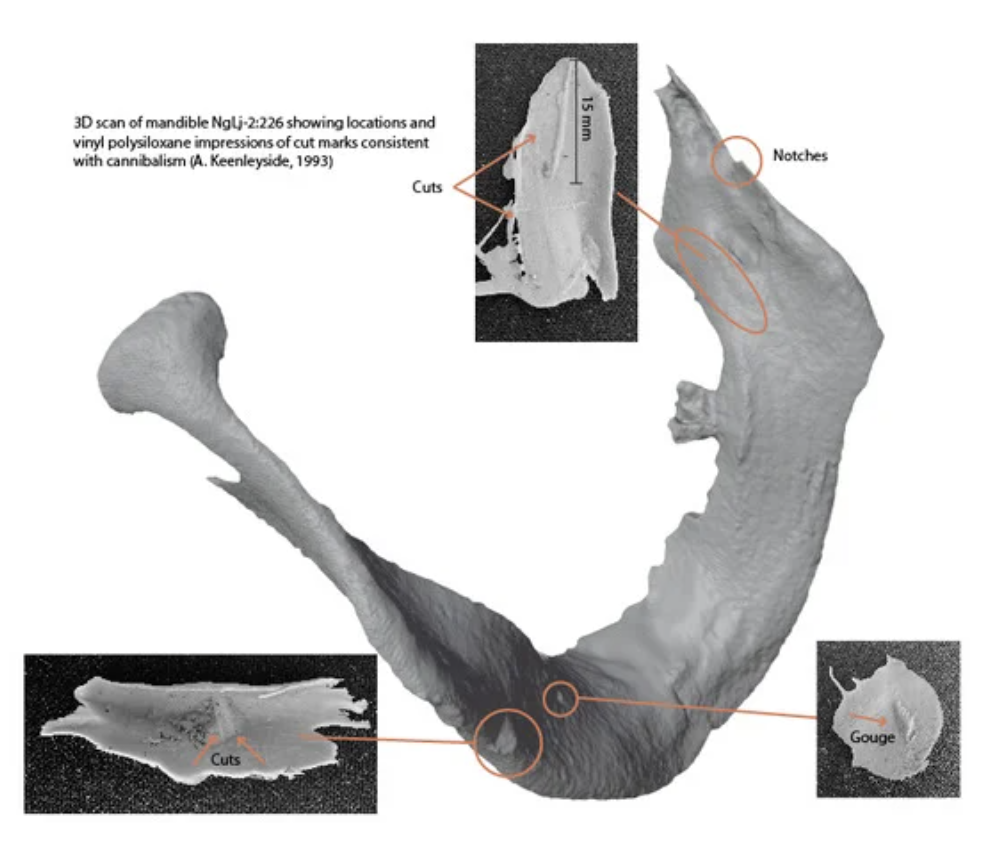

In the 1850s Inuit told searchers they had seen evidence that survivors had resorted to cannibalism, shocking some Europeans. Those accounts were fully corroborated in 1997 by the late Dr. Anne Keenleyside who found cut marks on nearly one-quarter of the human bones at NgLj-2, proving that the bodies of at least four of the men who died there had been subject to cannibalism.

Fitzjames’ mandible is one of the bones exhibiting multiple cut marks, demonstrating that after his death his body was subject to cannibalism. “This shows that he predeceased at least some of the other sailors who perished, and that neither rank nor status was the governing principle in the final desperate days of the expedition as they strove to save themselves,” said Stenton.

19th century Europeans believed that all cannibalism was morally reprehensible, but the researchers emphasize that we now understand much more about what is known as survival or starvation cannibalism and can empathize with those forced to resort to it. “It demonstrates the level of desperation that the Franklin sailors must have felt to do something they would have considered abhorrent,” said Dr. Robert Park, Waterloo anthropology professor. “Ever since the expedition disappeared into the Arctic 179 years ago there has been widespread interest in its ultimate fate, generating many speculative books and articles and, most recently, a popular television miniseries which turned it into a horror story with cannibalism as one of its themes. Meticulous archaeological research like this shows that the true story is just as interesting, and that there is still more to learn,” said Park.

The remains of Fitzjames and the other sailors who perished with him now rest in a memorial cairn at the site with a commemorative plaque.

Descendants of members of the Franklin expedition are encouraged to contact Stenton. “We are extremely grateful to this family for sharing their history with us and for providing DNA samples, and welcome opportunities to work with other descendants of members of the Franklin expedition to see if their DNA can be used to identify other individuals.”

“Identification of a Senior Officer from Sir John Franklin's Northwest Passage Expedition” by Stenton, Fratpietro and Park was published in the “Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.” The research was funded by the Government of Nunavut and the University of Waterloo.

Story posted @ uwaterloo.ca/news

Lakehead University civil engineering Dr. Ahmed Elshaer (centre back row) is joined by members of his team at the Structural and Wind Engineering Research Laboratory (SWERL). From left: Magdy Alanani, a post-doctoral fellow; Mostafa Elhadary, Amir Ali, Tristen Brown and Raghdah Al-Chalabi, all PhD candidates

Lakehead University civil engineering Dr. Ahmed Elshaer (centre back row) is joined by members of his team at the Structural and Wind Engineering Research Laboratory (SWERL). From left: Magdy Alanani, a post-doctoral fellow; Mostafa Elhadary, Amir Ali, Tristen Brown and Raghdah Al-Chalabi, all PhD candidates

Maliheh Ghorbankhani was also involved in the project. As a master's student, she helped update the qualitative and quantitative data. And as part of her thesis research, she delved into the report's outcomes and interviewed both the participants and the users of the report card.

Maliheh Ghorbankhani was also involved in the project. As a master's student, she helped update the qualitative and quantitative data. And as part of her thesis research, she delved into the report's outcomes and interviewed both the participants and the users of the report card.

“They took the project on very personal topics instead of just reporting on research other people had done,” says Dowsley, an associate professor in anthropology, and the department of geography and the environment at Lakehead University. “The original thought was that they would want to make a video about one of the research projects the community was already involved in. But they decided to take a more personal direction, looking at history and culture, which was very interesting.”

“They took the project on very personal topics instead of just reporting on research other people had done,” says Dowsley, an associate professor in anthropology, and the department of geography and the environment at Lakehead University. “The original thought was that they would want to make a video about one of the research projects the community was already involved in. But they decided to take a more personal direction, looking at history and culture, which was very interesting.”