Research in Action: Let's go down the rabbit hole!

Published in The Chronicle Journal Friday, March 31, 2023.

BY JULIO HELENO GOMES

Who faked the moon landing? Who assassinated the popular politician? Who rigged the election? Faced with nine possible “suspects,” your challenge is to deduce who among a varied cast of characters (such as the Deep State, Space Aliens or the Mainstream Media) are the “real conspirators.”

That's the intriguing concept behind a board game created by a Lakehead University researcher and his international collaborators.

But along with being a game of deduction and bluffing, CLUE-ANON is also a research tool and a catalyst for what may be uncomfortable but necessary interactions with family and friends.

“We wanted to make a game to see if we could understand what made conspiracy theories so attractive,” says Dr. Max Haiven. “We're trying to understand not only if conspiracy theories are right or wrong, but what makes them appealing and why people believe them.

“The game is actually an excuse to start a conversation.”

Haiven, an associate professor who teaches in the English department and on Social Justice issues, is a cultural theorist whose focus includes conspiracies, gamification and capitalism in a digital age. He has been working with collaborators in sociology and political science to develop a tool that combines the murder-mystery of the classic board game CLUE from the angle of the QAnon conspiracy fantasy.

The idea grew from podcasts involving authors, activists and experts on conspiracy theories, as well as Haiven's own students expressing a reluctance to go home for the holidays and deal with family members talking about the dangers of coronavirus vaccines or child sex-trafficking rings operating out of pizza parlours. Board games, Haiven says, is a neutral activity where you can engage in this awkward dialogue.

“The idea is by playing it you can take on different roles, kind of understand the problem and have a conversation about it in a way that's not 'Oh, you're right! You're wrong!' ” he says. “It's actually trying to understand it from a sociological perspective: why is it that people believe in this, what forces are at work, why do we have this problem right now.”

The project hits close to home for Stella Lawson, a graduate assistant who works at Haiven’s lab. A master's student in Social Justice, Lawson was born and raised in the U.S. and saw first-hand “how dangerous collective delusions can be when aligned with the power structures of Christian dominance,” not unlike what's happening today. Lawson, who moved to Canada five years ago, has worked on social issues and became interested in Haiven's work after hearing his podcasts. What solidified this interest was when a neighbour became enmeshed in conspiratorial thinking during the COVID lockdown.

“It was a very confusing time. Many groups were falling into very binary thinking about (the pandemic) and the only people I heard talking about it with any nuance and complexity were on that podcast,” Lawson says.

“The first time Max showed me CLUE-ANON – before it even had a name -- I knew he was onto something. We played a few rounds and discussed it late into the night. That is a big part of the reason I enrolled at Lakehead,” adds Lawson, whom Haiven credits with devising the name.

“The first time Max showed me CLUE-ANON – before it even had a name -- I knew he was onto something. We played a few rounds and discussed it late into the night. That is a big part of the reason I enrolled at Lakehead,” adds Lawson, whom Haiven credits with devising the name.

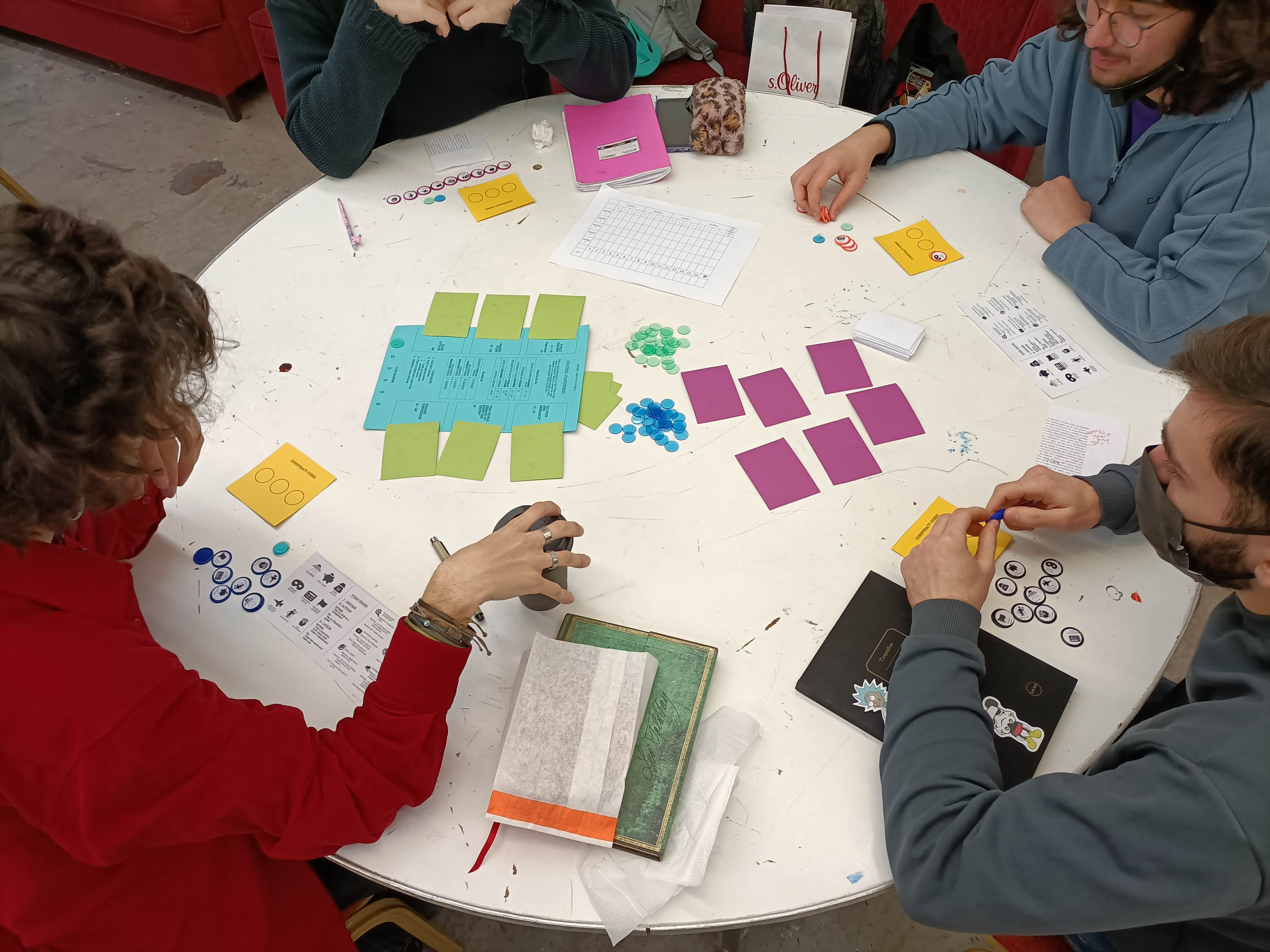

Along with reviewing the literature exploring how games have been used to advance social justice, Lawson has also been play-testing it. Development of CLUE-ANON began two years ago and the game has been revised 15 times as participants (some as far-flung as the U.S., England, Denmark and Singapore) provide feedback. Is it fun? Is the game a realistic depiction of what it's like to believe in conspiracies? How does it reflect what they've encountered with acquaintances who express such “crackpot” notions?

“Not everyone is falling for the same conspiracy theories, but around the world such beliefs are very, very common,” Haiven states, adding that the goal is not to demonize those who embrace way-out-there ideas. “We're not interested in calling people who believe in conspiracies idiots or fools or misguided. We begin from the position that, actually, there are real conspiracies – that's the way the power has always worked in human societies. Smaller groups of people get together and they make plans to maintain or extend their power. That's normal.

“But there is something very dangerous about many of the conspiracy theories that circulate today, because they take the form of complete fantasy worlds and they really misunderstand how power works in a society.”

CLUE-ANON is useful to engage people who might be susceptible to falling down the proverbial rabbit hole and getting obsessed with a conspiracy theory.

“It's not a game that's going to pull anyone out if they're already convinced of their conspiracy theory,” Haiven says. "CLUE-ANON aims to prevent people falling down the ‘rabbit hole’ in the first place, rather than to rescue people. You need other techniques to rescue people from those conspiracies.”

Haiven co-directs the ReImaging Value Action Lab and is Canada Research Chair in Radical Imagination, which he defines as a way to bring people together to explore how society could be different and ponder what prevents change. During his research term in 2023, when he is not teaching in Thunder Bay, he is based in Berlin, meeting like-minded researchers and examining Germany's thriving games industry.

CLUE-ANON is an imperfect game. It's still being refined and Haiven hopes it can be released to the public in a downloadable package. He may also approach a manufacturer to develop a version with detailed artwork and solid pieces.

Games-based research is about more than having fun, Lawson says. It's a way to relate to urgent issues in society, to find a way to make social movements more compelling and effective.

“I still haven't played CLUE-ANON with that neighbour,” Lawson admits. “But I have learned that one of the best interventions into the dangers of conspiratorial thinking is to keep showing up in the relationship rather than further isolating people, which largely drives them further into communities with profoundly concerning and distorted ideas.

“I can see how game-playing is a way of maintaining the connection and how even those who largely eschew conspiracies can benefit from and even gain empathy around the seduction of group-think so we can become better at intervening.”

Research in Action highlights the work of Lakehead University in various fields of research.

What's the game?

Following are highlights of CLUE-ANON board game developed by Max Haiven and colleagues:

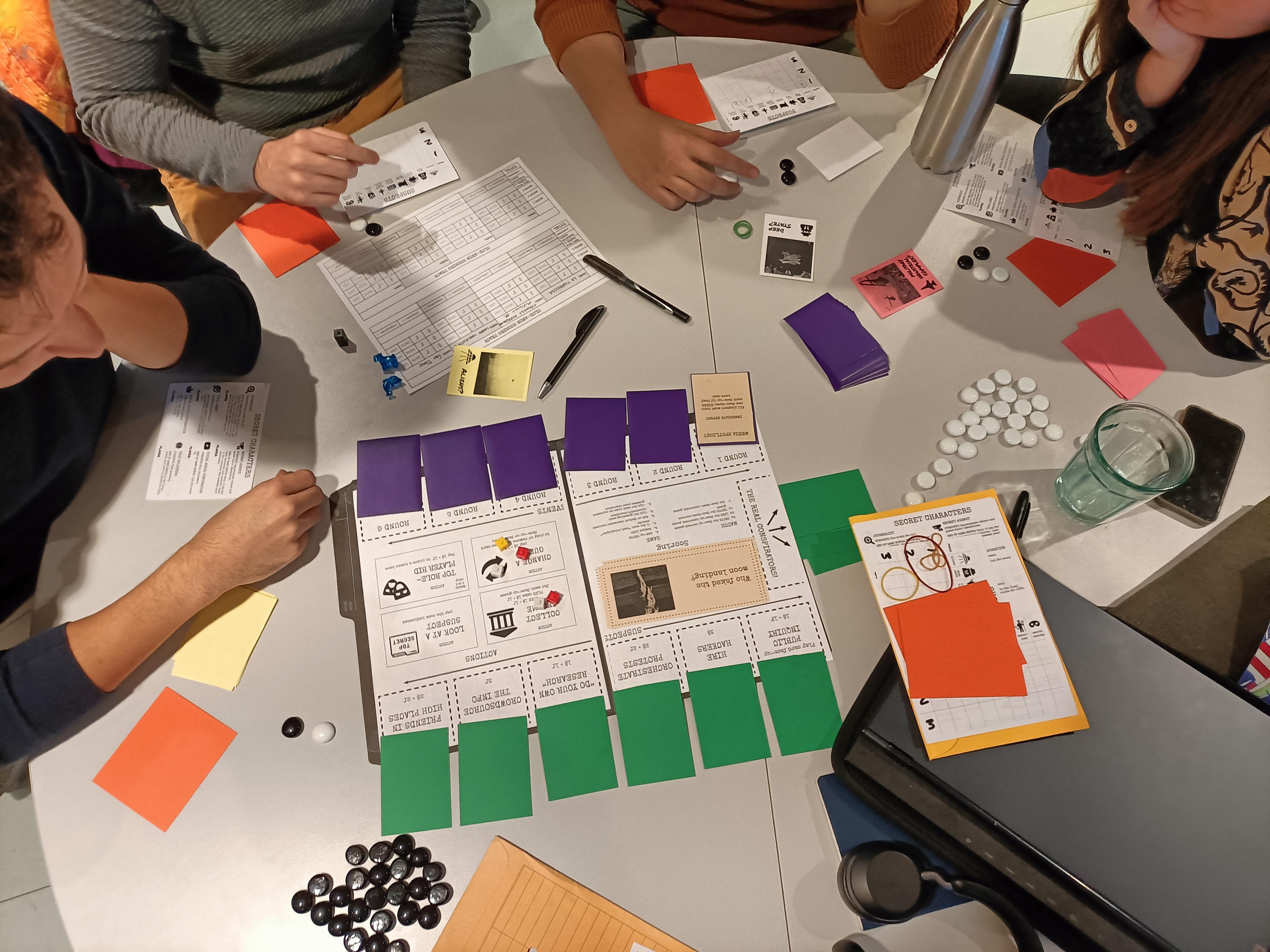

• involves 3-4 players, across two or three “matches”

• nine possible “suspects” on cards (eg, the Deep State, Independent Journalist, Space Aliens, an Evil Corporation, Satanist, the Mainstream Media, True Believer, Troll Army)

• of these nine, three are “real conspirators”, placed under the board until the end of match

• remaining six are arranged face-down on board

• players have six turns to use in-game resources (eg, Money and Followers) to try to figure out the three hidden “real conspirators” and solve the conspiracy

• bluffing -- players can gain more money and followers if they publicly announce they believe one or more suspect is involved in the conspiracy, even if they have little or no evidence

• the twist -- a successful player’s strategy will be influenced by the character they have been randomly assigned which they keep secret until the end

• all players have the incentive to pretend to be one of the nine possible “suspects”

• at the end of the game, after all the conspiracies are solved, players can try to guess one another's characters for extra points