Dr. Rob Stewart Spearheads Efforts to Protect Lake Superior

OVERVIEW:

- Dr. Rob Stewart leads the Freshwater Coastal Management Research Group and coordinates Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) along the Canadian north shore of Lake Superior

- Harbours along Lake Superior were heavily polluted as a result of mining and forestry operations and industrial development

- The work of RAPs, combined with government regulation, has made Lake Superior harbours safe for swimming and a source of drinking water

- Dr. Stewart, in collaboration with RAPs, is investigating emerging global threats to the health of Lake Superior

- Lakehead researchers are also working with Indigenous communities with the goal of restoring Lake Nipigon's ecosystem

"The best way to experience the magnificence of Lake Superior is to paddle to the last chain of islands before you hit open water," says Dr. Rob Stewart.

He's an associate professor of geography & the environment who feels most at home on the lake.

"It's amazing to be 10 km offshore in a kayak and have an otter pop up and hiss at you."

His career has been devoted to working with local communities to protect the watersheds and coastal environments of the Lake Superior Basin.

"Lake Superior is the headwater of all the Great Lakes, and its health determines the future of all the Great Lakes," he explains.

Dr. Stewart leads Lakehead's Freshwater Coastal Management Research Group and coordinates Remedial Action Plans (RAPs) along the Canadian north shore of Lake Superior.

"We identify environmental problems, monitor them, and then work on lake restoration," he says.

Through the determination of communities and researchers, there's been great success in removing pollutants from Lake Superior.

"When I was growing up, places like Thunder Bay, Nipigon, and Red Rock had working harbours.

There was foam, oil, and tree bark floating on the water because industries like pulp mills and mines would discharge effluents directly into the lake.

Today, you can swim in these harbours and use them for drinking water because of intense government regulation and the clean-up efforts of RAP groups."

Community members belonging to the Jackfish Bay Area of Concern RAP discuss next steps to deal with legacy contaminants discharged into Lake Superior by the Terrace Bay Pulp and Paper Mill. "Remedial Action Plan groups try to reduce conflict between communities and governments over problems that can't be immediately resolved," Dr. Stewart says.

Now, Lake Superior RAPs are equally concerned with emerging threats to the lake that don't have simple solutions and that require cooperation between countries.

"We're investigating how to deal with invasive species, airborne mercury travelling from China and India, and climate change—Lake Superior is the fastest warming Great Lake."

Uncovering the Story of Lake Nipigon

Dr. Stewart's research extends beyond Lake Superior.

He's excited to be working with Indigenous communities in the Lake Nipigon area to trace the history of this freshwater lake and how it's changed over the past 200 years.

"Lake Nipigon was intensely developed in the 1940s. Large forestry and mining operations were set up near the lake's shoreline.

The provincial government also built a hydroelectric dam that diverted massive amounts of water from the Arctic watershed into Lake Nipigon. This changed the lake's ecosystem dramatically."

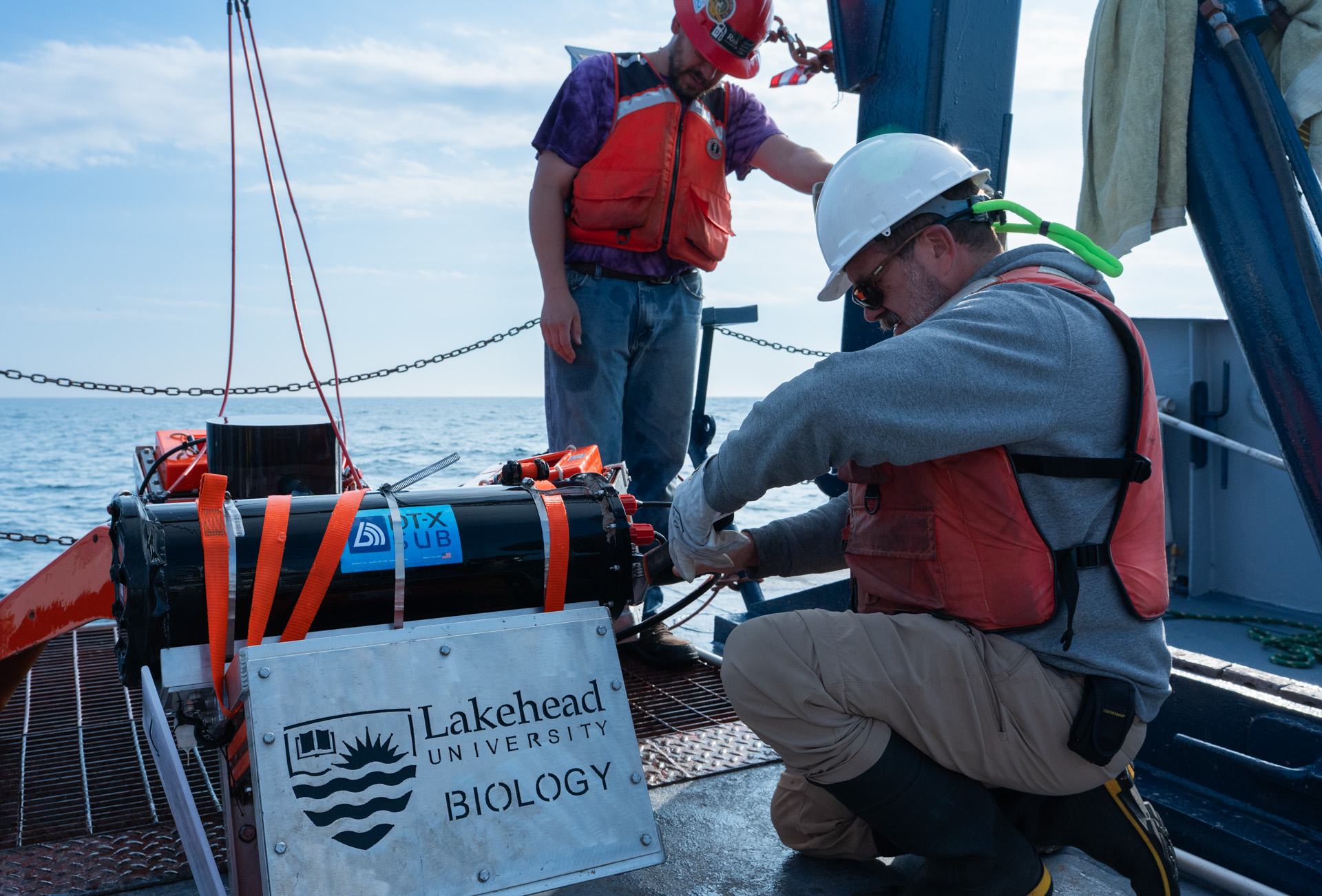

Above, the Nipigon Guardians Team (researchers from Lakehead, York University, and Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek First Nation) collect sediment core samples. "We want to empower Indigenous communities with data to verify what they've been saying all along about the negative effects of hydro dams on Lake Nipigon."

The high levels of silt and nutrients in the Arctic Watershed were too much for a freshwater body like Lake Nipigon to absorb.

"The silt covered up fish spawning grounds, and the overabundance of nutrients created toxic algae blooms. The dam also caused erosion and raised the level of the lake, which released more sediment and nutrients."

Until recently, Indigenous people were forced to stand by and see their lake degraded because they had no say over how it was developed.

"Now, First Nations want the full story of the lake's changes backed up with scientific data," Dr. Stewart says. "Our 'Lake Nipigon Cumulative Impacts Partnership' will help provide this information."

Dr. Stewart's Freshwater Coastal Management Research Group has built landscape features to filter stormwater before it reaches Lake Superior. They've also restored riverbanks and coastal habitats for fish and wildlife. For instance, constructing a new channel for fish to swim through (see above).

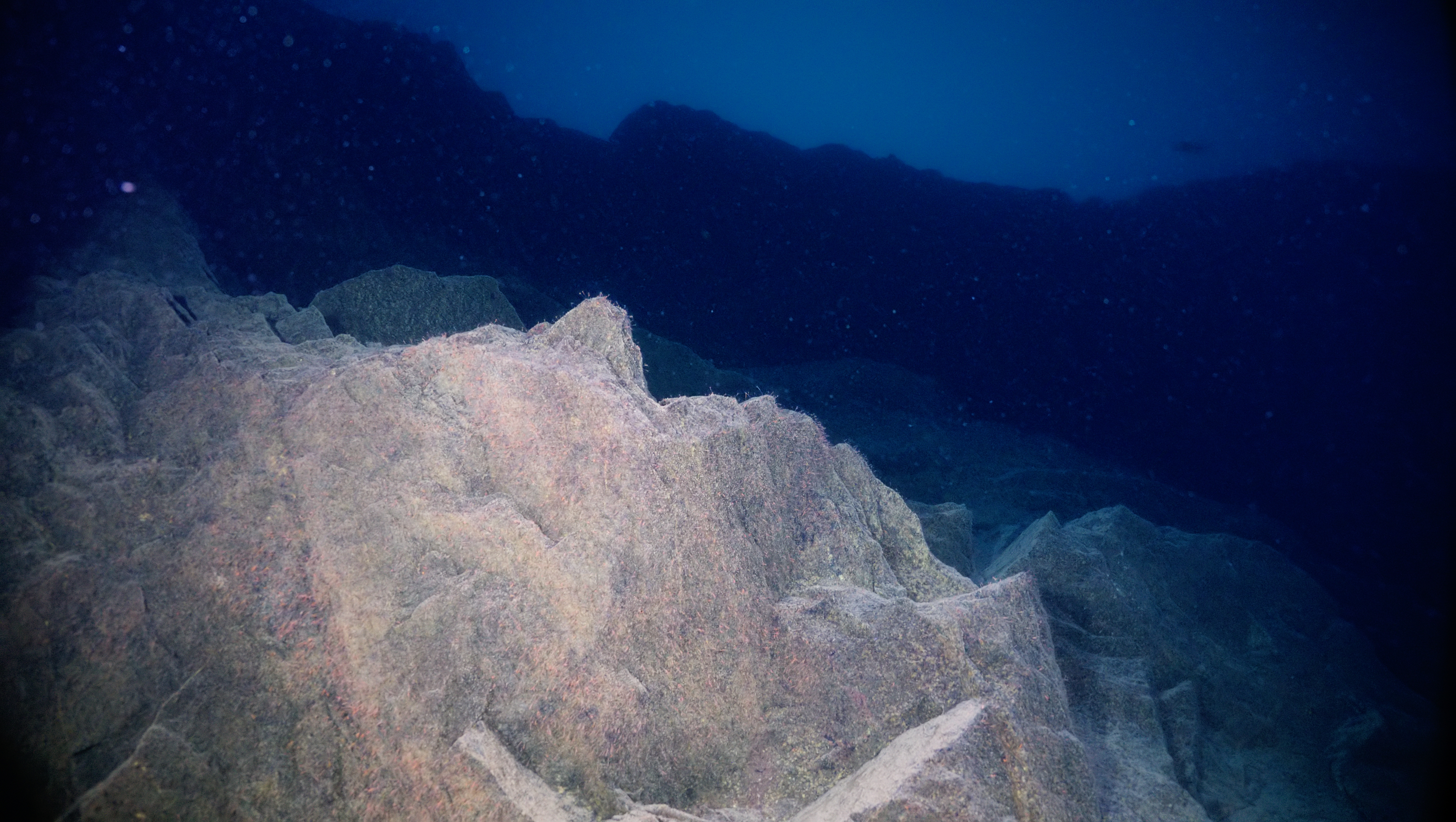

His research team is doing this by tracking the movement of fish in the lake and by taking sediment samples from the lake floor.

"We'll analyze the sediment to determine the nutrients, plants, aquatic life, and toxins present in Lake Nipigon at different time periods."

After all the evidence is gathered, communities will pinpoint areas of Lake Nipigon where the environment has been adversely affected by development and by pollution, such as arsenic contamination from mills. Then, they'll advocate to have them restored.

"They want to build healthy communities with clean water and land for their youth," Dr. Stewart says.

Save Our Remarkable Lakes

Current projects being led by North Shore of Lake Superior RAPs include shoreline naturalization and monitoring beaches closed because of high E.coli levels. "We also watch for new technology that may help with future lake restoration efforts," Dr. Stewart says.

He encourages local citizens to get involved in sustaining our region's waterways by joining an environmental community group or by becoming a member of one of the north shore's Remedial Action Plan groups.

"The number-one thing, though, is to connect with our lakes in your own way. Go for a canoe ride with a friend, take your kids fishing, or walk along one of the beaches."

Dr. Stewart's Lake Nipigon Cumulative Impacts Partnership research is funded by an NSERC Alliance Grant, the Indigenous Guardians Network, the First Nations Environmental Contaminants Program (Health Canada), and by Biinjitiwaabik Zaaging Anishinaabek. He has received funding for his Lake Superior research initiatives from the Great Lakes Freshwater Ecosystem Initiative, which is part of the Government of Canada's Freshwater Action Plan.