The Culture of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence

Sexual violence is rooted in power, control, and entitlement. When someone engages in sexually violent behaviour, they are disregarding the needs, boundaries, and autonomy of another person or person(s), and are instead choosing to act in their own self-interest. Individually, this may appear to be reflection of a personal flaw or failing on the part of the perpetrator.

However, the frequency of sexual violence victimization, as well as who commits sexually violent acts against whom, complicates the issue. Therefore, feminist scholars, criminologists, and sociologists have argued that sexual and gender-based violence has social and political causes, rather than just interpersonal.

The culture of sexual violence is commonly known as "rape culture", wherein rape and sexual violence is normalized, minimized, and even encouraged (Maxwell & Scott, 2014; Ryan, 2011). A rape culture is perpetuated through both small, everyday actions and larger acts of violence (Gravey, 2019). If you are interested in learning more about rape culture, consider completing our Module on this topic.

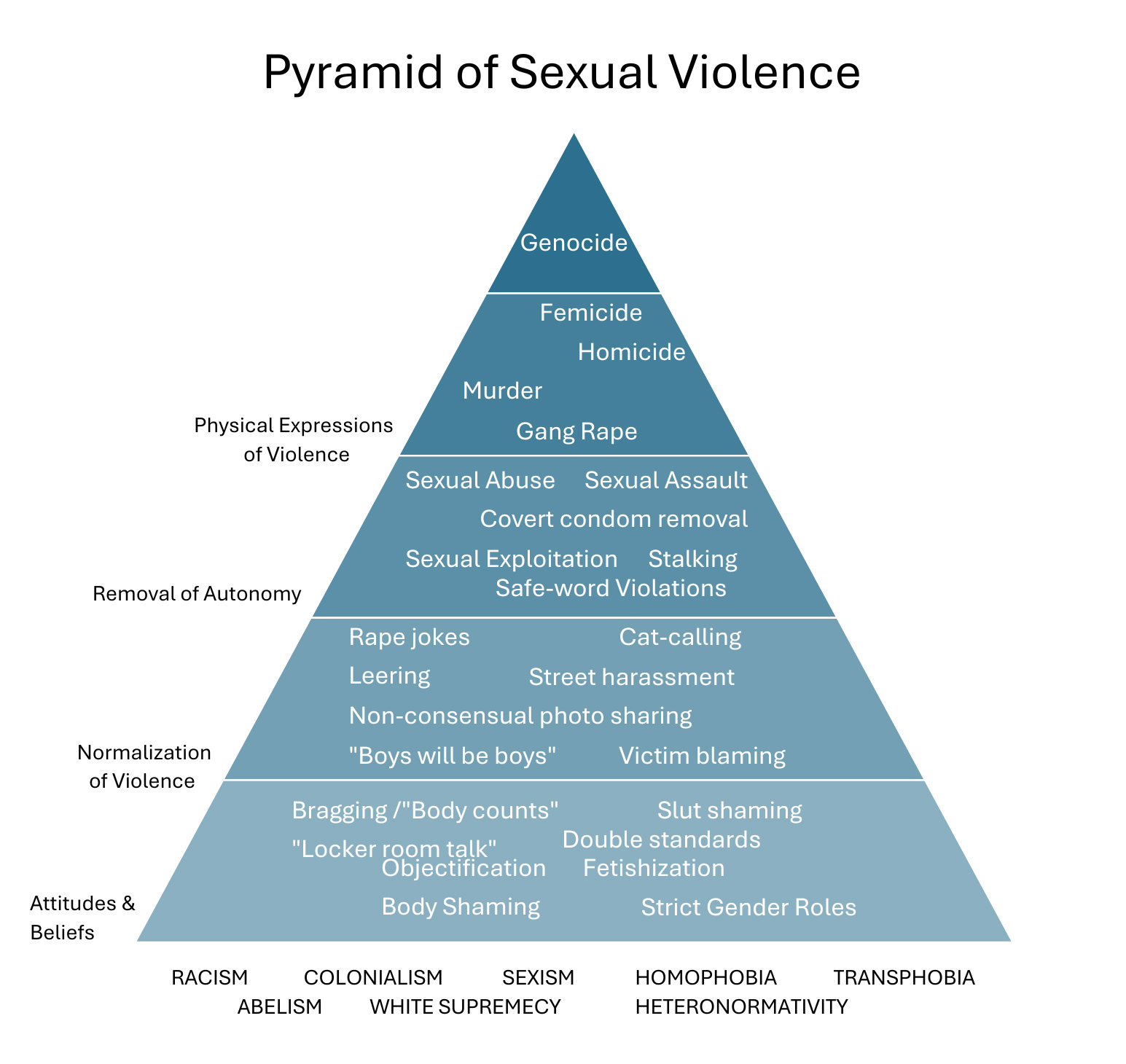

One way that we can understand how rape culture persists is through "The Pyramid of Sexual Violence", which is a tool developed by anti-sexual violence educators to help make the connection between different forms of sexual violence clearer. It illustrates that our foundational attitudes and beliefs can contribute to an environment where sexual violence is allowed to continue.

We can think of society as existing with "layers" of beliefs that make up how the world "works" and how we behave. Therefore, the foundation of a western colonial state such as Canada is informed by prejudiced belief systems and structures of oppression. These systems of oppression have, over time, established that certain behaviours are acceptable or "normal". Things like making jokes about date rape, domestic violence, or jokes mocking the culture of consent can be found easily in pop culture and media (seriously, it took us one google search to find all of these examples). Rape and sexual assault is minimized, and victims are routinely blamed for their victimization. You have likely heard (or even said) things like this in your life in casual conversation with friends, peers, family, or co-workers. The reason for this is not because you are a terrible person, but because you have been told that these actions are just "jokes", "not that serious", and that other people are "too easily offended".

However, these behaviours are, at their core, dehumanizing and ostracizing. They create hierarchies of value and autonomy across gender, race, sexuality, ability, and class lines. These structures create privilege for some, while actively and intentionally oppressing others. This is, in part, why those who are systematically oppressed by structural violence are therefore more likely to experience sexual victimization (Marx et al., 2024; Mellins et al., 2017). The pyramid helps us to understand why the small, everyday things that don't seem too serious actually support and uphold the severe forms of violence that millions of people experience.

This also means we can use this knowledge to intervene and challenge harmful and violence structures. The closer to the bottom of the pyramid we are, the easier we can step-in and intervene to help prevent sexual violence. A big part of the puzzle is challenging systems like racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, etc.

Why? Because if we can destabilize this foundation, everything above it becomes unacceptable in our society. If we hold each other accountable for the small moments of dehumanization of others, we establish a new baseline of "normal" behaviours. In doing so, we can work to create environments where sexual violence is never justifiable, and where community members are holding each other, and themselves, accountable for the harm they cause. It is not realistic to believe we will never have harm in a society, but we can reduce the amount of harm we are willing to accept as expected. More than 11 million Canadians have experienced SGBV which we believe is far too much harm.

Other Ways to Make Change

Hold Yourself Accountable

The reality is that anyone is capable of being sexually violent. This means that the responsibility is on each of us to challenge any feelings of entitlement we might feel towards people's time, affection, attention, and bodies. We also need to commit to respecting the physical, emotional, and intimate boundaries of others, regardless of our individual wants. Learn how to cope with rejection, rather than making other people responsible for your anger, hurt, or disappointment. If someone tells you that you have been sexually violent or inappropriate and caused them harm, do not get defensive. You have the chance to learn and do better. The person is telling you that you hurt them because they care about you and respect you enough to believe you can change and grown – prove them right.

Be Open-minded

When someone presents us with a new way of thinking about things, or a new perspective on the world that challenges our old one – don't write it off automatically. University is a place for you to learn more about the world and about viewpoints which differ from yours. Most of us have been taught a worldview which dehumanizes and minimizes people who are different to ourselves, and we all have unconscious biases. Learning to live alongside and care about people who look, think, and speak differently from you is essential. Assess how the music, television, and movies you currently engage with portray sexual violence. Do they mock it? Minimize it? Do they take it seriously? Challenge yourself to seek out media that does not contribute to rape culture, and media that actively combats rape culture and rape myths. Recognize that the words and phrases we use can be harmful and contribute to rape culture. Take stock of the words and phrases you use. Do you celebrate men who have sex while judging women who have sex? Do you discuss gender in traditional, binary ways? Do you repeat casual racist stereotypes? Do you have and hold assumptions about who is victimized? Do you intentionally misgender other people? You don't have to have "perfect" language to discuss the issue of SGBV, but you should be open and willing to stop using phrases, language, or terms you've been told are harmful.

Don't Assume

Never assume to have consent. Just because you are in a relationship, have had sex before, or have talked about having sex before, does not mean you have consent. Consent is not something that is always "on" the table until someone tells you its "off". Consent is an active, on-going, voluntary, enthusiastic practice. Do not assume you "get" what consent is all about. It is a nuanced and complex concept which is not universally understood or communicated. Something you may belief to be a clear indicator of consent may be a clear indicator of non-consent for your partner. Communicate about consent explicitly and directly and make it clear "no" is an acceptable answer. Practice this in all your relationships and interactions, including non-sexual ones. Do not assume you can have some of your friends' fries, ask them if they mind and respect it if they say "no". Ignoring boundaries in our everyday activities sets us up for ignoring boundaries in our more intimate activities.

Challenge Victim Blaming

Listen to and believe a survivor when they disclose to you. Many survivors are experiencing complex emotions around a traumatic event, and they may not always express it the same way or the way you believe they should. You may feel like you need more information to really "understand" how sexual violence happened, or to believe a victim. Ample evidence has shown that roughly 2-4% of SGBV reports are false, which is consistent will all other forms of violence crime. You would never question if your friend had been mugged, or their car had been broken into. You would not immediately assume they were lying, or they must have done something to cause it. Only for sexual violence do we hold victims to an unrealistic and unachievable standard of being "perfect" to be legitimately victimized. Instead of questioning choices made by someone who experienced sexual violence, extend empathy and compassion for their victimization. Understand that no one is ever responsible for something someone else chose to do to them. The only person responsible is the perpetrator.

Be a Leader

If you feel comfortable and safe doing so, stepping up and being a good bystander is essential in combatting rape culture. Challenge the violence which is shared casually (and perhaps unintentionally) in your normal daily conversations. Step in when you notice someone seems to be unsafe (you can learn more about bystander practices on our D2L site!). You can volunteer and get involved in local communities and efforts which address SGBV. If you're in Thunder Bay, consider volunteering with the Office of Human Rights and Equity or Gender Equity Center/Pride Central. If you're in Orillia consider getting involved with LUSU Orillia. You can also get involved in your local community, donate to organizations that support survivors of SGBV, join protests, sign petitions – the ways you can get involved are endless. Every person who is involved in challenging rape culture contributes to shifting the culture to one which is more inclusive and safer for everyone.

Sources:

Gavey, N. (2019). The gender of rape culture: Revisiting the cultural scaffolding of rape. In Just Sex? (2nd ed., pp. 227–259). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429443220-13

Marx, R. A., Maffini, C. S., & Peña, F. J. (2024). Understanding Nonbinary College Students' Experiences on College Campuses: An Exploratory Study of Mental Health, Campus Involvement, Victimization, and Safety. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 17(3), 330–345. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000422

Maxwell, L., & Scott, G. (2014). A review of the role of radical feminist theories in the understanding of rape myth acceptance. The Journal of Sexual Aggression, 20(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2013.773384

Mellins, C. A., Walsh, K., Sarvet, A. L., Wall, M., Gilbert, L., Santelli, J. S., Thompson, M., Wilson, P. A., Khan, S., Benson, S., Bah, K., Kaufman, K. A., Reardon, L., & Hirsch, J. S. (2017). Sexual assault incidents among college undergraduates: Prevalence and factors associated with risk. PloS One, 12(11), e0186471–e0186471. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186471

Ryan, K. M. (2011). The Relationship between Rape Myths and Sexual Scripts: The Social Construction of Rape. Sex Roles, 65(11–12), 774–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0033-2