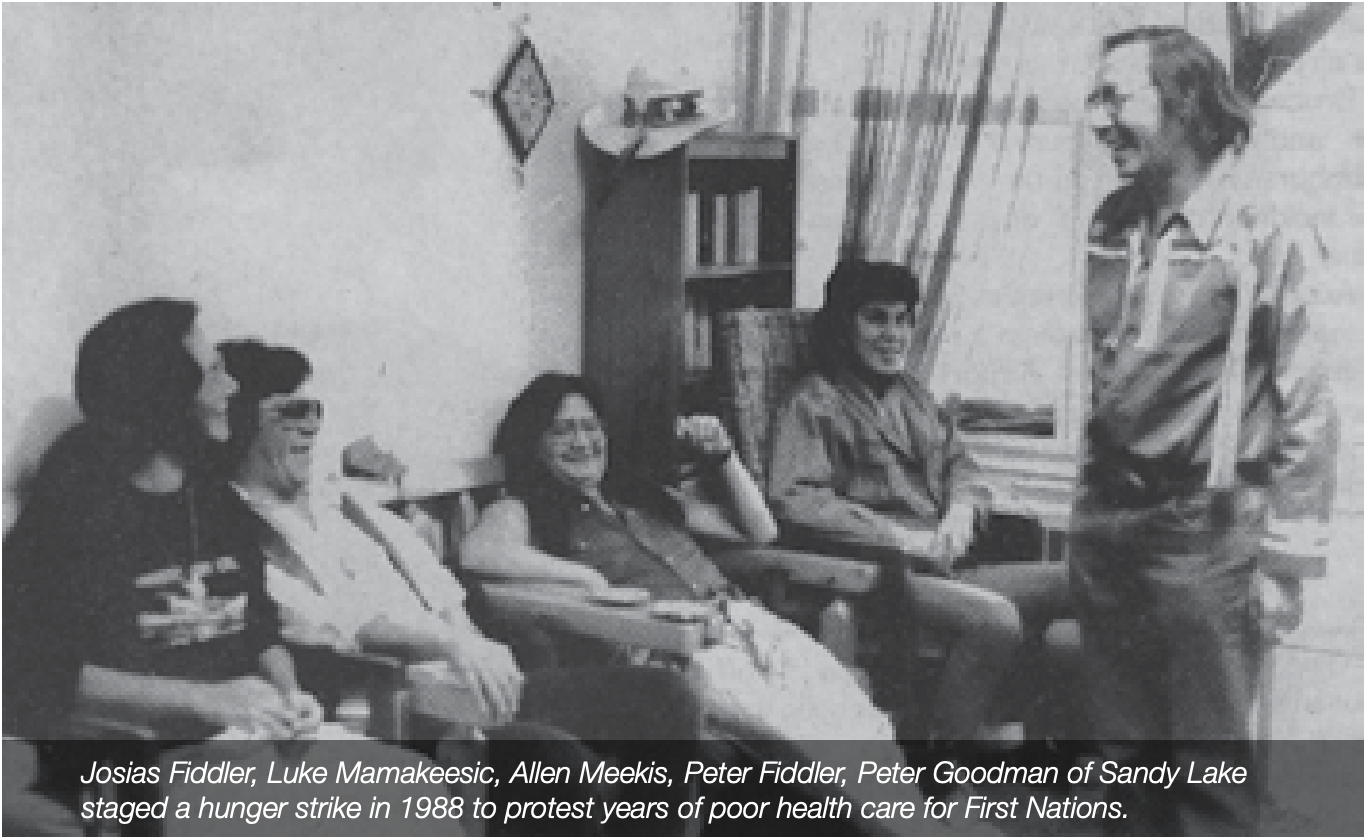

In 1988, Chief Josias Fiddler, head of Sandy Lake First Nation, travelled over 300 km to Sioux Lookout, Ontario. He wasn’t there for work or a vacation – he was there to begin a hunger strike.

Newspaper coverage of the hunger strike helped draw attention to the dire health care situation in Sandy Lake First Nation.

Taking part with him in this high-stakes protest were fellow band members Peter Goodman, Allan Meekis, Peter Fiddler, and Luke Mamakeesic. The Sandy Lake Five wanted to draw attention to decades of abysmal health care services in their community. There was no hospital in Sandy Lake. Many had witnessed family and friends die because they didn't have access to proper medical care.

Federal and provincial governments were playing a pass the buck game trying to spend as little money as possible in Indigenous communities, Dr. Travis Hay says.

Dr. Hay is a historian with Lakehead University's history department and Indigenous learning department who specializes in Canadian federal Indian policy and settler colonialism. He is also a Lakehead University alumnus with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts in History.

He began researching the hunger strike in 2019 and he's written a book – The Science of Settler Colonialism – that will be released in September 2021 by the University of Manitoba Press.

"I study archival records," says Dr. Hay, "but these can only tell half of the story."

Dr. Travis Hay graduated from Lakehead with an HBA in History in 2010 and an MA in History in 2012.

Josias Fiddler's wife, Teri Redsky Fiddler, has served as the project Elder, collaborating with Dr. Hay to reconstruct and provide context for the events explored in the book. Teri is also an educator, an advocate, and an important figure in Nishnawbe Aski Nation's Health Transformation initiative. Her perspective is especially important since Josias passed away in 2012 and can no longer take part in this conversation.

Dr. Hay is also supervising Skye Fiddler, Josias and Teri Fiddler’s granddaughter, as she pursues her honours degree in Indigenous Learning at Lakehead. Skye’s research will share even more stories of her grandfather’s life and legacy in Northwestern Ontario.

“The hunger strike was a major moment in the history of Canadian medicine,” Dr. Hay says.

A History of Substandard Health Care

Since the 1960s, Ontario medical schools had been sending nursing and medical students north to train them. It was a practice that created a different – and lesser – level of health care in Sandy Lake.

The situation wasn’t helped by the many university and government researchers who parachuted into the community to conduct experiments in the midst of stark inequities.

Teri Redsky Fiddler (right) married her late husband Josias Fiddler (left) in 1969. She misses him every day and often returns to their home community of Sandy Lake First Nation.

Chief Fiddler was keenly aware that Indigenous peoples across the country were used as guinea pigs. He himself was a survivor of a residential school and had spent time in a racially segregated Indian hospital. Students and patients in these institutions were historically exploited by scientists to conduct research trials.

“Often, it was scientific experimentation without consent or with considerable coercion,” Dr. Hay explains. These ranged from malnutrition experiments aimed at mass producing cheap food to vaccination experiments.

In fact, Canadian science’s understanding of respiratory infections, tuberculosis quarantine protocols, and vaccination – information relevant to COVID-19 – come directly from the study of Indigenous peoples.

One horrifying experiment from the 1970s involved researchers exposing young children to the cold, because they were convinced that northern Indigenous people could recover more quickly from frostbite than non-Indigenous people.

Research projects in Sandy Lake and other Indigenous communities forced people to weigh potential health care funding from the projects against their willingness to become the subjects of medical research.

By 1988, Chief Fiddler had had enough. The main demand of the Sandy Lake Five was that government medical services representatives fly to Northwestern Ontario to discuss the state of health care in their community.

Within a few days, the hunger strikers were able to secure a meeting and news media had begun covering the story. Their actions prompted the formation of the Scott-McKay-Bain Health Panel to review health services in Northwestern Ontario.

The courage of the Sandy Lake Five also led directly to the establishment of First Nations Health Authorities, organizations that transferred some of the responsibility for health care policies into the hands of Indigenous communities.

Another outcome of the hunger strike was the construction of Sioux Lookout’s Meno Ya Win Health Centre. This 80-bed primary health care facility takes a holistic approach to health and wellness and serves Indigenous communities throughout the region, as well as Sioux Lookout residents.

Despite the victories that followed in the wake of the protest, Sandy Lake still faced challenges, including continued experimentation by researchers.

In the 1990s, the Province of Ontario paid $750,000 to researchers to find the ‘thrifty gene’ in the DNA of Sandy Lake band members – a gene they believed was responsible for higher rates of diabetes in Indigenous people.

The community was skeptical, but agreed to the research in order to receive health care funding.

“The study put Canadian genomics science on the map after researchers claimed they’d found the gene,” Dr. Hay says.

“Sandy Lake became known as the community where people got diabetes not because of the cost of food, inadequate health care, or lack of infrastructure, but because of this gene.”

It was not long before the research was thoroughly discredited and it’s now infamous for the scientific racism it embodied.

Even today, Sandy Lake community members find themselves in a precarious situation. They have no choice but to travel great distances by plane or winter roads to receive essential health care.

It’s my hope that The Science of Settler Colonialism will expose the myth of universal health care in Northwestern Ontario,” Dr. Hay says, “and bring to light an entrenched policy of treaty breaking.